Friday Reading: The Story of Robert Smalls, An Escaped Slave Turned Union War Hero And U.S. Congressman

The internet is abuzz today in regards to some comments Francis Ford Coppola made regarding movies today. A statement made prior by Martin Scorcese, and echoed by other great directors since- that movies today suck and are unoriginal.

Is he wrong?

Don't get me wrong. I love Marvel movies. I love comic book movies in general. The characters are foils very similar to Greek heroes and tragic heroes, the themes and messages are steeped in virtue and timeless debates of morality.

That's all a fancy way of saying they are deeper than just some comic book characters running around beating up bad guys and saving planet Earth.

But Coppola does have a point. A very good one.

How many times can the same movie, with the same characters, and the same themes and scenarios be made?

Are we that soft-skulled of a species that as long as enough time has passed, and enough marketing dollars have been spent, we will fall for the trick?

Answer: yes.

I mean how many times have they remade Batman now? Excuse me, The Batman.

10? 12?

What about Spider Man?

I remember a few years ago they put out two The Hulk movies back to back in like two years because they thought the first one flopped.

Where is the originality? Where is the creativity?

Where is the fuckin beef?

I don't think it's a lack of creativity. I think people are just so fuckin lazy today.

Nobody reads, nobody wants to think. They want to take the easiest route to get the quickest result. Which often times equates to recycling the same proven garbage with new "stars" and altered titles over and over and over again.

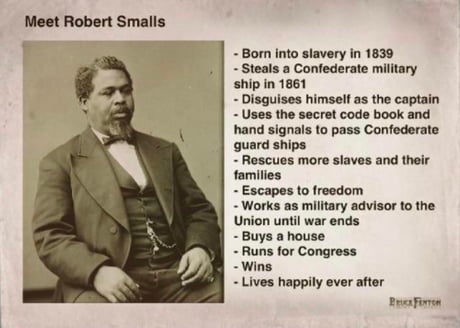

A couple months ago I came across a meme on Instagram that seemed too incredible to be true.

It said something to the effect of, "Hey Hollywood, we have 30 Avengers movies, how about doing one on a real-life super hero?"

Above this picture.

I admittedly had never heard the name Robert Smalls before. Never mind all of his accolades listed on this.

And I am very weary of the memes posted on the internet because I know for a fact that Abraham Lincoln and Tupac Shakur both couldn't have said and been quoted as saying the same thing.

(Sidebar- do people not realize that half of these celebrity quote memes floating around the internet are straight up garbage? You know the ones I'm talking about. The philosophical quotes attritubuted to Johnny Depp, or Marilyn Monroe. "Dance like you've never been hurt before. Love like nobody is watching."

So I did some research.

PBS, Battlefields.org, and Biography all had decent pieces on him.

And surprise surprise, Youtube actually had a couple good recaps as well.

As it turns out, it was all true.

Smalls was born on April 5, 1839, behind his owner’s city house at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, S.C. His mother, Lydia, served in the house but grew up in the fields, where, at the age of nine, she was taken from her own family on the Sea Islands. It is not clear who Smalls’ father was. Some say it was his owner, John McKee; others, his son Henry; still others, the plantation manager, Patrick Smalls. What is clear is that the McKee family favored Robert Smalls over the other slave children, so much so that his mother worried he would reach manhood without grasping the horrors of the institution into which he was born. To educate him, she arranged for him to be sent into the fields to work and watch slaves at “the whipping post.”

“The result of this lesson led Robert to defiance,” wrote great-granddaughter Helen Boulware Moore and historian W. Marvin Dulaney, and he “frequently found himself in the Beaufort jail.” If anything, Smalls’ mother’s plan had worked too well, so that “fear[ing] for her son’s safety … she asked McKee to allow Smalls to go to Charleston to be rented out to work.” Again her wish was granted. By the time Smalls turned 19, he had tried his hand at a number of city jobs and was allowed to keep one dollar of his wages a week (his owner took the rest). Far more valuable was the education he received on the water; few knew Charleston harbor better than Robert Smalls.

It’s where he earned his job on the Planter. It’s also where he met his wife, Hannah, a slave of the Kingman family working at a Charleston hotel. With their owners’ permission, the two moved into an apartment together and had two children: Elizabeth and Robert Jr. Well aware this was no guarantee of a permanent union, Smalls asked his wife’s owner if he could purchase his family outright; they agreed but at a steep price: $800. Smalls only had $100. “How long would it take [him] to save up another $700?” Moore and Dulaney ask. Unwittingly, Smalls’ “look-enough-alike,” Captain Rylea, gave him his best backup

Is this not the perfect introduction?

A slave, born into a terrible situation, with no real way out, is "the favorite" of the family who owned him. So he received preferential treatment.

His mother, also a slave, feared he'd be indoctrinated to believe his owners weren't bad people, and that slavery wasn't a horrific concept. So she sends him to the fields to watch his relatives and friends get the shit beat out of them by rednecks on power trips.

Over time, he grows up, marries, has a couple of kids (all the property of his owners) and decides to ask them, after saving up an astounding $100, how much to buy his family's freedom.

$800 he's told.

A ridiculous amount. One his owners knew would never be attainable, yet would remain a glimmer of hope to keep him working hard.

Our story begins in the second full year of the war. It is May 12, 1862, and the Union Navy has set up a blockade around much of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. Inside it, the Confederates are dug in defending Charleston, S.C., and its coastal waters, dense with island forts, including Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired exactly one year, one month, before. Attached to Brig. Gen. Roswell Ripley’s command is the C.S.S. Planter, a “first-class coastwise steamer” hewn locally for the cotton trade out of “live oak and red cedar,” according to testimony given in a U.S. House Naval Affairs Committee report 20 years later.

After two weeks of supplying various island points, the Planter returns to the Charleston docks by nightfall. It is due to go out again the next morning and so is heavily armed, including approximately 200 rounds of ammunition, a 32-pound pivot gun, a 24-pound howitzer and four other guns, among them one that had been dented in the original attack on Sumter. In between drop-offs, the three white officers on board (Capt. C.J. Relyea, pilot Samuel H. Smith and engineer Zerich Pitcher) make the fateful decision to disembark for the night — either for a party or to visit family — leaving the crew’s eight slave members behind. If caught, Capt. Relyea could face court-martial — that’s how much he trusts them.

At the top of the list is Robert Smalls, a 22-year-old mulatto slave who’s been sailing these waters since he was a teenager: intelligent and resourceful, defiant with compassion, an expert navigator with a family yearning to be free. According to the 1883 Naval Committee report, Smalls serves as the ship’s “virtual pilot,”but because only whites can rank, he is slotted as “wheelman.” Smalls not only acts the part; he looks it, as well. He is often teased about his resemblance to Capt. Relyea: Is it his skin, his frame or both? The true joke, though, is Smalls’ to spring, for what none of the officers know is that he has been planning for this moment for weeks and is willing to use every weapon on board to see it through.

Like any great drama or thriller, the protagonist concocts a plan, and then waits what seems an eternity for just the right moment to spring it.

That opportunity is at hand on the night of May 12. Once the white officers are on shore, Smalls confides his plan to the other slaves on board. According to the Naval Committee report, two choose to stay behind. “The design was hazardous in the extreme,” it states, and Smalls and his men have no intention of being taken alive; either they will escape or use whatever guns and ammunition they have to fight and, if necessary, sink their ship. “Failure and detection would have been certain death,” the Navy report makes plain. “Fearful was the venture, but it was made.”

At 2:00 a.m. on May 13, Smalls dons Capt. Rylea’s straw hat and orders the Planter’s skeleton crew to put up the boiler and hoist the South Carolina and Confederate flags as decoys. Easing out of the dock, in view of Gen. Ripley’s headquarters, they pause at the West Atlantic Wharf to pick up Smalls’ wife and children, along with four other women, three men and another child.

At 3:25 a.m., the Planter accelerates “her perilous adventure,” the Navy report continues (it reads more like a Robert Louis Stevenson novel). From the pilot house, Smalls blows the ship’s whistle while passing Confederate Forts Johnson and, at 4:15 a.m., Fort Sumter, “as cooly as if General Ripley was on board.” Smalls not only knows all the right Navy signals to flash; he even folds his arms like Capt. Rylea, so that in the shadows of dawn, he passes convincingly for white.

Bad ass. Ballsy as fuck. Genius.

But not even close to done.

Smalls sailed the boat north.

In The Negro’s Civil War, the dean of Civil War studies James McPherson quotes the following eyewitness account: “Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, ‘I see something that looks like a white flag’; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and ‘de heart of de Souf,’ generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, ‘Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!’ ” That man is Robert Smalls, and he and his family and the entire slave crew of the Planter are now free.

You would think this would have been enough right?

He'd gotten his family and himself to freedom in the north. He was not only a free man, but a celebrated one. The Union Army made him a poster boy and word of his heroic story spread.

But Smalls was just getting started.

Du Pont is similarly impressed, and the next day writes a letter to the Navy secretary in Washington, stating, “Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feet so skillfully, informed me of [the capture of the Sumter gun], presuming it would be a matter of interest.” He “is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been.”

Smalls may not have had the $700 he needed to purchase his family’s freedom before the war; now, because of his bravery and his inability to purchase his wife, the U.S. Congress on May 30, 1862, passed a private bill authorizing the Navy to appraise the Planter and award Smalls and his crew half the proceeds for “rescuing her from the enemies of the Government.” Smalls received $1,500 personally, enough to purchase his former owner’s house in Beaufort off the tax rolls following the war, though according to the later Naval Affairs Committee report, his pay should have been substantially higher.

The Confederates seemed to know this already; after Smalls’ escape, biographer Andrew Billingsley notes, they put a $4,000 bounty on his head. Still, those on the scene had a hard time explaining how slaves pulled off such a feat;

You would think again that being flush with cash, having his freedom, and not having to fear for his safety as long as he stayed in the north that Smalls would hang it up and call it a day no?

Instead, he decided to enlist and head back to war to fight for his country.

In the North, Smalls was feted as a hero and personally lobbied the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to begin enlisting black soldiers. After President Lincoln acted a few months later, Smalls was said to have recruited 5,000 soldiers by himself. In October 1862, he returned to the Planter as pilot as part of Admiral Du Pont’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. According to the 1883 Naval Affairs Committee report, Smalls was engaged in approximately 17 military actions, including the April 7, 1863, assault on Fort Sumter and the attack at Folly Island Creek, S.C., two months later, where he assumed command of the Planter when, under “very hot fire,” its white captain became so “demoralized” he hid in the “coal-bunker.” For his valiancy, Smalls was promoted to the rank of captain himself, and from December 1863 on, earned $150 a month, making him one of the highest-paid black soldiers of the war.

Add war hero to his list of accolades.

But he STILL wasn't done.

Following the war, Smalls continued to push the boundaries of freedom as a first-generation black politician, serving in the South Carolina state assembly and senate, and for five nonconsecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1874-1886) before watching his state rollback Reconstruction in a revised 1895 constitution that stripped blacks of their voting rights.

He died in Beaufort on February 22, 1915, in the same house which he had been born a slave in, that he had gone back and purchased after the war. (POWER MOVE).

He was buried behind a bust at the Tabernacle Baptist Church.

In the face of the rise of Jim Crow, Smalls stood firm as an unyielding advocate for the political rights of African Americans: “My race needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country. It proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

There it is assholes.

There's your Hollywood blockbuster served up on a silver platter.

If I knew how to write screenplays I would take this and run with it myself. Write a marvelous script, present it to Smalls' descendants, ask for their blessing and cut them in on whatever they wanted.

I'd cast Idris Elba or Michael B. Jordan to play Robert, tab Ryan Coogler to direct. And sit back and watch a movie masterpiece be made.

And you know how I know this is a sure thing? Because some of the best movies are based on true stories. Think about it- Gladiator, Schindler's List, American Sniper, Dark Knight Rises (jk).

But you get it.

If you're as fascinated by Robert Smalls' story as I am/was, check out this book - Be Free Or Die.

and this Ted Talk.

p.s. - is Francis familiar with some of the movies his nephew Nic has starred in?