We Need To Start Tarring And Feathering Baseball Writers Who Submit Unexplainable HOF Ballots, Starting With The Guy Who Didn't Vote For Ichiro

The Sporting News - Ichiro Suzuki made his name in Japan and his mark in Seattle. Now, the 51-year old finds a new home: Cooperstown. The longtime Mariners supernova — who also played for the Yankees and Marlins across a glittering 19-year MLB career — headlines the 2025 Baseball Hall of Fame class.

A one-time AL MVP — and one of just two players to win MVP and Rookie of the Year in the same season — Suzuki is one of baseball's greatest-ever imports. With Tuesday's announcement, he becomes the first Japanese player inducted into Cooperstown. The fact that he did so on the first ballot is simply the cherry on top, another bit of history for the 10-time All-Star and single-season hit king.

But more history beckoned for Ichiro had the voters – or rather, one voter — been kinder. The multifaceted outfielder fell just one vote shy of being voted in unanimously, the rarest of honors, even among baseball's elite.

At present moment, it's unclear which BBWAA member left Ichiro off of their Hall of Fame ballot.

Suzuki entered Tuesday evening on a high, with a 100% success rate across ballots released to the public. Suzuki was the standout name on a list filled with them and represented one of only three players on the writers ballot to win an MVP (alongside Rodriguez and Jimmy Rollins).

However, it seems one voter wasn't convinced of his credentials. Suzuki was named on 324 of 325 ballots. One voter opted to keep him out of baseball's eternal home.

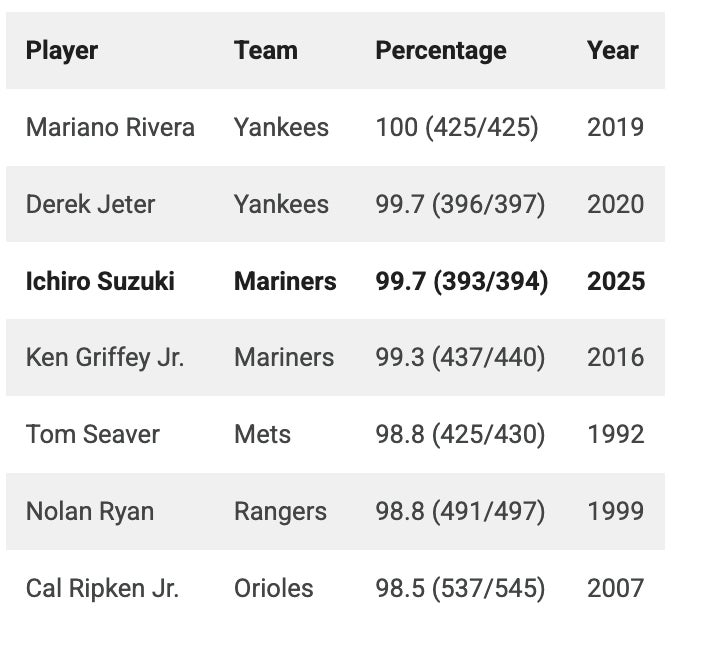

He's not the only former Seattle star to receive such treatment. In 2016, Ken Griffey Jr. was inducted into Cooperstown. The Kid was kept off just three of the 440 ballots used (99.3%).

The Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA), in their infinite wisdom, have once again proven just how out of touch they are with the game they claim to cover. Ichiro Suzuki, gets inducted into the Hall of Fame on his first ballot. The guy who would have easily become the all-time hits king, had he played in MLB longer, and one of the most electrifying players in history, AND a global ambassador for the sport.

He should’ve waltzed into Cooperstown with a standing ovation from every corner of the baseball world. But no, one self-important baseball writer decides to leave him off their ballot. For what, exactly?

A personal vendetta?

Some loser's jealousy that resulted in a power trip that allows them to whisper to his other loser big journalist friends, "it was me"?

What the fuck are we doing here?

What makes it even worse is we allow them to hide behind the shield of anonymity.

For context, Ichiro got to 4,257 professional hits in 3,363 games, 14,339 plate appearances, and 13,107 at-bats. While finishing with 4,256 hits, Rose also set all-time Major League records with 3,562 games, 15,890 plate appearances, and 14,053 at-bats.

I've written extensively here what a crime it is that baseball barred Rose from being enshrined-

The fact that Ichiro eclipsed Rose's staggering stat line, and did it in 1,500 fewer plate appearances is one of those stats that doesn't make sense.

Ichiro's entire resume is one of those that should be a blueprint for what an unanimous vote should be. And it begs the question, if he's not worthy of receiving 100% of the vote, than who is?

(Sidebar - want a good chuckle? Look at this graph.)

If that doesn't prove what little weasels baseball writers are than I don't what other proof you need.

The entire system is fucked. It makes zero sense.

The folks who get to decide who makes it into the Hall of Fame have never played the game. Not at the professional level, not at the college level, probably not even in a competitive little league game where their parents weren’t yelling at them to lean in and “take one for the team” just so they could get on base.

These are people who sit behind desks and write about the game, but they’ve never worn a glove or stepped up to the plate. Yet they’ve somehow earned the right to decide whether a guy who spent his entire career proving he was among the very best to ever play the game deserves a bronze plaque.

What the hell are we doing here?

Talk about outrageous hypocrisy here. This is like draft-dodging politicians deciding who goes to war. Imagine if every general in the U.S. Army was somebody who’d never been within a hundred miles of a battlefield, yet they were the ones calling the shots.

This is the same kind of logic that lets guys like Ken Griffey Jr. (who was a no-brainer first-ballot Hall of Famer) get shorted votes by someone with a grudge or an agenda.

I asked my father for help writing this blog because he's basically an expert historian when it comes to all things Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio. And Williams notoriously HATED baseball writers, and was famous for his criticism of the power they wielded, and lack of accountability they faced.

He sent me what amounted to an essay- so I am going to copy and paste his response to me here-

"Why on Earth wasn't Joe DiMaggio a first ballot hall of famer?

Your question took me by surprise as I had always assumed that DiMaggio had been a first-ballot Hall of Famer, as he ought to have been, so I did a little research and found that, indeed, DiMaggio was not a first-ballot Hall of Famer, nor even second, but made it on his third ballot, in 1955. For some reason, DiMaggio also got one vote in 1945, though he was not yet retired, but the method of election differed that year than the method we're familiar with now. That year, voting had two rounds. In the first, there was no specific ballot as each member of the Baseball Writers Association of America submitted a slate of names as nominations and then the BBWAA created a ballot listing the top twenty players from the nominating ballots. (As a side note, those nominating ballots contained a few players who might have been listed as a personal favor to a player since they clearly seem to lack Hall of Fame credentials: players like Steve Yerkes, who appeared in 711 games over seven seasons and retired with a .268 average and a .677 OPS; judging by his appearances on leader boards for defense, he seems to have been a solid second baseman but was not stellar enough in the field to suggest that he was named for glove work.)

In 1953, DiMaggio's first year on the ballot after he retired, it seems that the general impression was that he was a lock for the Hall. (Unlike now, there was no five-year waiting period then for election to the Hall of Fame; that was added for the 1954 election, though anyone who received at least 100 votes in previous elections was grandfathered in and eligible for consideration.) The Sporting News was so confident that he'd be elected that, just before the BBWAA announced the results of balloting, it ran a long article headlined "DiMag Heads for Speedy Election to Shrine" and beginning, "Although precedent is against the election of a player to the Hall of Fame only one year after his retirement, Joe DiMaggio is regarded as the leading candidate (for election)." The Sporting News went on to say that early returns seemed to bear out that DiMaggio would certainly gain the necessary 75 percent of votes for election. As it turned out, he did not and, in fact, finished eighth in voting, earning only 44 percent of the votes in a year in which writers sent two players to Cooperstown, pitcher Dizzy Dean, who led all players that year with 79.2 percent of the vote in his ninth year on the ballot, and outfielder Al Simmons, who eked into the Hall with his name on 75.4 percent of the ballots (he got 199 votes in a year players needed 198 to gain election); it was also his ninth year on the ballot.

After DiMaggio failed to gain election, observers put his failure down to a couple of reasons: One, that voters resisted electing someone only a year after his retirement. To that point, only one player had ever gained election to the Hall of Fame a year after his retirement, Lou Gehrig, but he was elected in a special ballot when writers became concerned that, because he was seriously ill, he would not live long enough to see what pretty much everyone assumed would be his eventual enshrinement. He was elected in 1939, shortly after his final game, and died in 1941 just shy of his 38th birthday.

Secondly, the premature reports that early voting returns suggested that DiMaggio would gain election may have hurt him (though it turned out those early reports were likely false, since the BBWAA members who counted the ballots reportedly didn’t open a single one until the day they sat down to count them all.) Writing in the New York Times after the full election results were in, sports columnist Arthur Daley said, "It probably didn’t help DiMaggio's cause one bit that a premature news service story blandly declared (he) was 'leading in the voting.' . . . The erroneous gun-jumping announcement harmed (DiMaggio) in two directions. It lulled some of his supporters into thinking he was so safely in that they could plug for someone else. It also created resentment elsewhere by making other writers feel that DiMaggio was being stampeded into the Hall. So they just refused to enter his name on the ten-name list."

DiMaggio also failed to make it the next year, in 1954, when voters did elect three players, Rabbit Maranville (in his 14th year on the ballot), Bill Dickey (in his ninth year) and Bill Terry (in his 14th year). DiMaggio finished fourth, earning mention on 69.4 percent of the ballots; his 175 votes were 14 less than the necessary 189. Again observers suggested that voters were more interested in recognizing players who had been waiting much longer than DiMaggio, and the balloting seems to bear that out: of the top 20 players who got votes, only seven had been on the ballot for less than ten years—in order of their vote totals for that year, they were DiMaggio, Ted Lyons (9 years),Hank Greenberg (7), Joe Cronin (8), Tony Lazzeri (9), Red Ruffing (7) and Duffy Lewis (8). Among the top 20 vote getters that year, every one of them eventually gained election to the Hall of Fame, save for Hank Gowdy, who was in his 13th year on the ballot that year but who never got more that 36 percent of the vote in any one of the 17 years he was on the ballot.

Other writers speculated that there was also a bias against New York players by voters who did not live on the east coast. Writing in the New York Daily News, columnist Jimmy Powers said, "Western critics over a period of time have taken cracks, not at Joe DiMaggio, but at his overly enthusiastic supporters in café society, in the Toots Shor and Lindy belts, where he was regularly on display night after night. . . . Joe, of course, is an innocent victim but this, I maintain, partially explains his weakness in the polls. . . " The Sporting News did observe, however, that DiMaggio at least had some solace for any disappointment he might have felt: "While the former Yankee star has his compensation for his '54 failure to attain the shrine, a honeymoon with the gorgeous and glamorous Marilyn Monroe, the motion picture star." DiMaggio and Monroe had married roughly ten days before the Hall of Fame voting results were released.

The next year, DiMaggio finally made it, earning mention on 88.8 percent of the ballots (he was listed on 223 of the 251 ballots)

This whole idea that the BBWAA has any business making these decisions needs to be reconsidered. Why don’t we just let retired players or other living members of the Hall of Fame decide who makes the cut? You know, like how a club works?

They know what’s real. They understand what the game means. These baseball writers? Throw them in the fuckin bathroom.

I still think to this day, one of the best suggestions/solutions to this all comes from Bill Simmons.

Simmons viewed the the Hall of Fame as something far bigger than just a plaque gallery. His point, boiled down, is that the Hall should function first and foremost as a museum that tells the complete story of the sport. The good, the bad, the weird, and even the scandalous.

In Simmons’s view, if you’re writing the story of baseball, you cannot leave out the complex figures (or eras) that helped shape it- whether those players are universally beloved or mired in controversy. By treating Cooperstown as a museum, you’re essentially saying you need to include the legends. Warts and all.

If there’s let's say, a home run king (or single-season home run record holder) who’s tied up in steroid allegations, you don’t just pretend he never existed. You display his story- achievements, controversies, and all, to educate future generations about what actually happened. Good museum exhibits aren’t about celebrating every piece of history; they’re about preserving and explaining it.

It should also reflect the evolution of the game.

Baseball is a constantly changing sport. Slow as molasses, but it's been around over a century and has come a long way. Whether it’s integration, expansion, shifts in training and technology, rule changes, or the more recent data-analytics revolution.

A museum approach brings those stories to life in context. Instead of using the Hall of Fame as a gatekeeping device (where some old-school writers arbitrarily keep out “tainted” players), they should instead present the facts: “Here’s what happened, why it happened, and how it impacted the sport.”

If the Hall of Fame acts like more of a museum, it’s not a few baseball writers policing the narrative.

It’s historians, fans, and the general baseball community contributing to all of the exhibits.

When you put someone like Ichiro in, you don’t just mention his fucking batting average and Gold Gloves, you also delve into how he altered perceptions of Japanese players in MLB, or how his style of hitting challenged decades-old norms about power vs. contact.

Simmons argued that Cooperstown should function like the Smithsonian of Baseball, and I agree. It should all be in there- the superstars, the antiheroes, the record-setters, the asterisks, and the off-field soap operas, all of it.

So you walk out with a richer understanding of the game. The Hall-of-Fame-as-museum model asks- how do we properly preserve the story of baseball for future generations? Instead of- “should we give so-and-so our personal seal of approval?”

This is a broken system, and it’s time we all admit it. Let’s stop letting a bunch of out-of-touch nerds decide who deserves to be immortalized in Cooperstown, because it’s becoming clearer every year that their judgment is, at best, questionable, and at worst, downright laughable.

Like the brilliant scene in Robert Redford's The Natural depicted, (Fun Fact - Redford based his portrayal of Hobbs as an homage to his childhood idol Ted Williams), these assholes legitimately consider themselves "guardians of the game", protectors of a game that isn't even theirs.

Here are some of the more absurd Ichiro stats and highlights. I'll pull some from a past blog I did about going down an Ichiro rabbithole one night at 3 in the morning.

The haters in the comment section (of the Instagram post, not this lovely website) are all saying the video is doctored up and Ichior didn't knock all those bats down consecutively, nor knock the lid off that trash can and then sink the next immediate throw inside of it.

But my eyes see none. That looks like the real deal to me.

I looked deeper into it and found this video on tik tok of him filling that trash can dozens of throws later

I did some more digging and found that both clips came from this Japanese tv commercial

Which immediately gave me Mike Vick Powerade commercial vibes

So I did some more digging. And found this ridiculous compilation somebody put together of him slashing and slapping

Then there was this one of him gunning out morons who thought they could run on him

And this top ten video capped by his All-Star Game in the park home run

Guy was the epitome of a freak show.

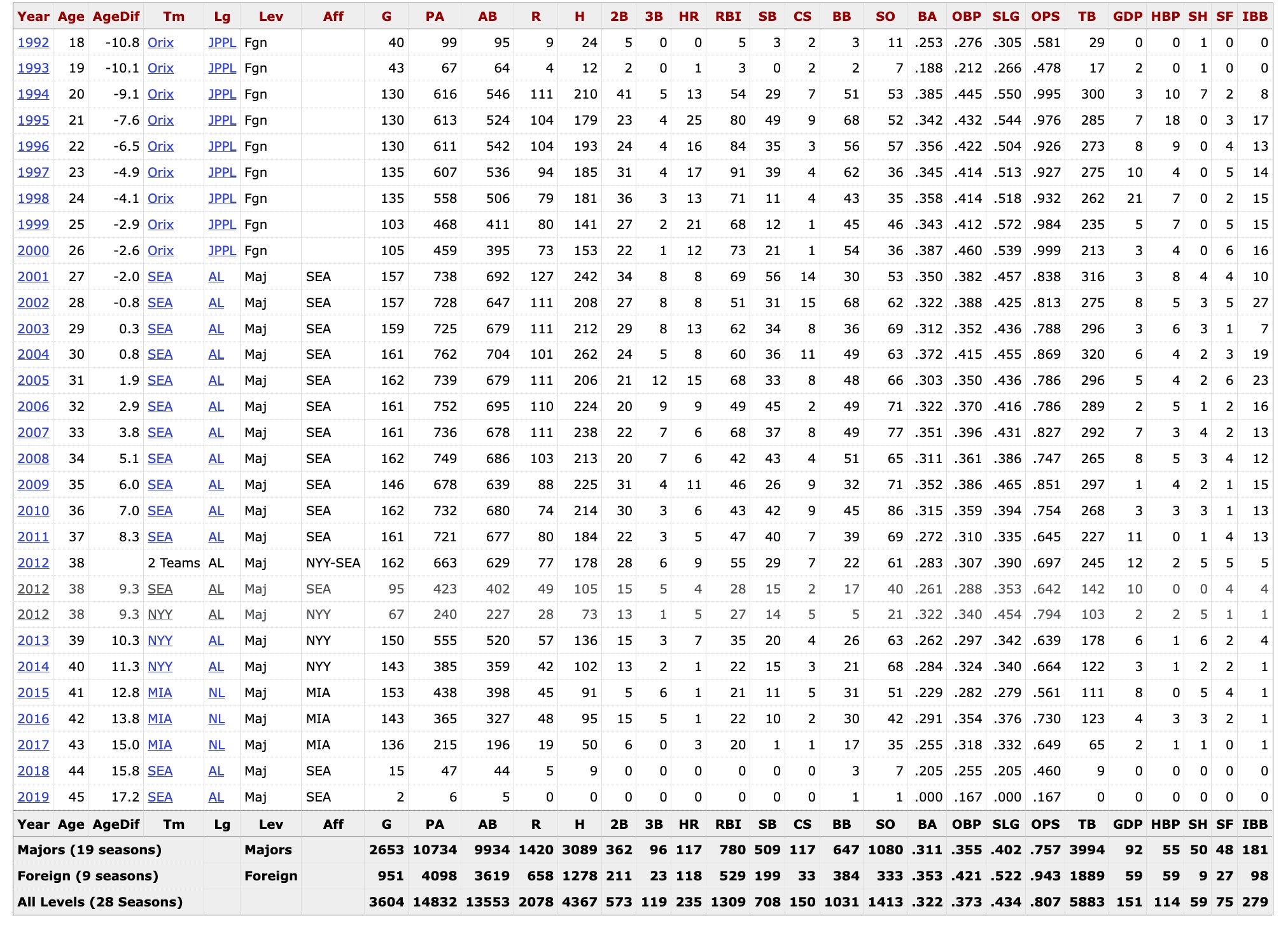

Look at these numbers -

His 3,089 hits in the Majors rank 22nd all-time, and his career .311 batting average ranks 13th highest among the 32 players in the 3,000-hit club. Because he was never a significant power hitter, with just 117 homers, or .01 yabo per at-bat, his .402 slugging percentage is the lowest among that elite group.

Ichiro reached 3,000 hits in 10,333 plate appearances and 2,452 games, the 13th and 14th quickest to do so for each, respectively.

Including his 1,278 hits over nine seasons in the Japan Pacific League, before he came to the Majors, Ichiro has 4,367 hits, 111 more than Pete Rose.

He won the American League batting title, the AL Rookie of the Year Award and the AL MVP Award in 2001, and he remains the only player in MLB history to win all three in his first season. (Fred Lynn is the only other player to win the Rookie of the Year Award and the MVP Award in the same season, doing so with the Red Sox in 1975.)

(Here's a great fun fact - Only once in his MLB career did Ichiro finish a game with his career batting average below .300. That came when he took an 0-for-4 in his second game as a rookie, making him 2-for-9 (.222) overall. He promptly went 2-for-4 in the next game and never looked back.)

Again, ABSOLUTE FREAK.

If those videos weren't enough for you, dive into this 32-minute gem.